Illyrian tribes in the 1st-2nd centuries CE

In the latter half of the 3rd century BC, several Illyrian tribes appeared to come together to establish a proto-state that extended from the central region of modern-day Albania to the Neretva River in Herzegovina. This political entity, led by King Agron, relied on piracy as a source of financing and was at the height of it’s power in 250-231 BC.

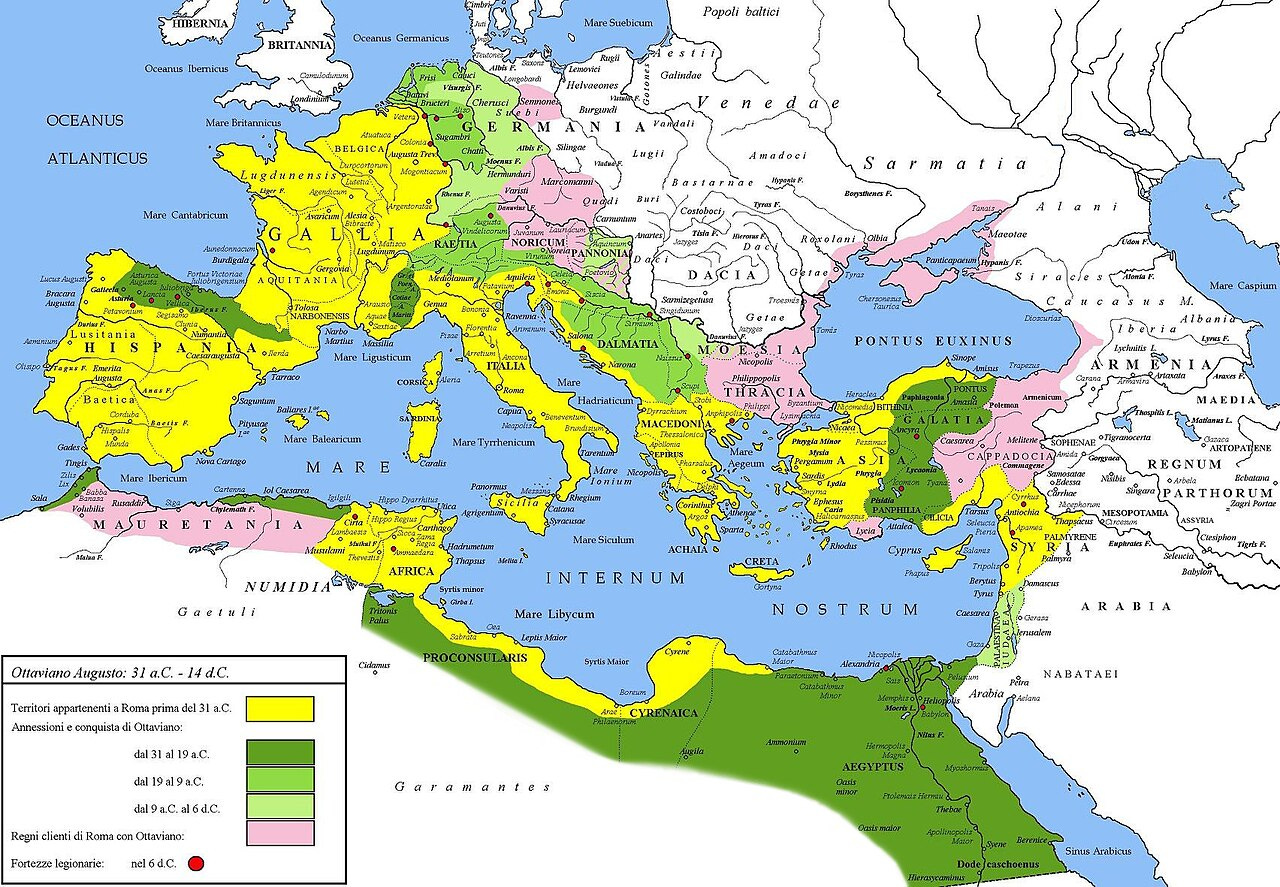

After Agron's death in 231 BC, his wife Teuta took over the regency for her stepson Pinnes. In the 2nd century BC, as documented by Polybius in The Histories, diplomatic exchanges between the Romans and Illyrians began. Rome conducted three campaigns during the Illyrian Wars of 229 BC, 219 BC, and 168 BC, aiming to curb piracy and secure the Adriatic for Roman trade. The initial campaign in 229 BC marked the first time the Roman Navy crossed the Adriatic for an invasion. Eventually, the Roman Republic subdued the Illyrians, and Augustus quashed an Illyrian revolt from 6-9 AD, leading to the division of Illyria into the northern province of Pannonia and the southern province of Dalmatia. With it, displacement of the Illyrian population.

Territorial absorption of Illyrian land didn’t fully occur until the rule of Emperor Augustus.

Despite the final installment of the ‘Illyrian’ war occurring in 168 BC, different parts of the region of the Southwest Balkans rose up against Roman rule for over 100 years.

Timeline of Illyrian-related Events:

156 BC: Dalmatae attack Illyrian subjects of Rome; Consul Gaius Marcius Figulus campaigns against them, eventually subduing the Dalmatae.

155 BC: Consul Scipio Nasica Corculum continues the suppression of the Dalmatae.

135 BC: Illyrian tribes Ardiaei and Palarii raid Roman Illyria; Rome levies an army, consul Servius Fulvius Flaccus marches against the Illyrians.

129 BC: Consul Gaius Sempronius Tuditanus and Tiberius Pandusa wage war against the Iapydes, potentially subjugating them.

119 BC: Consul Lucius Caecilius Metellus Dalmaticus wages war against the Dalmatae for triumph.

115 BC: Consul Marcus Aemilius Scaurus conducts operations against Ligures in Gallia Cisalpina and the Carni and Taurisci in Illyricum.

113 BC: Consul Gnaeus Papirius Carbo faces an invasion by the Cimbri in Illyricum and Noricum, resulting in defeat at the Battle of Noreia.

78–76 BC: Gaius Cosconius, as proconsul, fights for two years in Illyricum, reducing Dalmatia and seizing Salona (near modern day Split). The Roman settlement Colonia Martia Iulia Salona is later founded.

These events showcase a series of military campaigns, conflicts, and suppressions involving Illyrian tribes and Roman forces in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, which can only paint a picture of turmoil in the area. One must also accept that population loss was occurring on the Illyrian side during this time frame, this population loss, combined with Roman settlements kept driving the Illyrian culture to irrelevance and extinction.

Aquileia, a Roman town founded in 180/181 BC, served as a defensive outpost against hostile eastern peoples (not all Illyrian) like the Carni, Taurisci, Histri, and Iapydes.

The Carni (Celtic), settling in 186 BC, invaded northeastern Italy, prompting the Romans to establish Aquileia after forcing them back to the mountains. This turbulent landscape required Rome to make crucial decisions, including pacification efforts and the introduction of more settlers in strategic regions.

The establishment of Aquileia provides reasoning as to why Rome built settlements/colonies such as Salona in Illyricum. After pushing out the Carni, Rome settled 3,000 families in its foundation in response to the attempted settlement by approximately 12,000 Taurisci in 183 BC, Aquileia expanded further. By 169 BC, an additional 1,500 families were sent there.

Let’s take a moment to note what constituted of a “Roman family” as this allows us to translate ‘4,000 families’ into tangible populations and gives us insight to common shared challenges / makeups of surrounding groups which the Celts and Illyrians might also be experiencing: In the Roman Empire around 2nd-1st century BC, families faced the challenging reality of a life expectancy at birth estimated at 22–33 years. This context, coupled with high child mortality rates due to prevalent infectious diseases, underscored the resilience required for family life. Women, with life expectancies of twenty to thirty years, needed to give birth to between 4.5 and 6.5 children to maintain replacement levels; considering factors like divorce, widowhood, and sterility. To counteract the impact of early childhood deaths and ensure population growth, the birth rate likely needed to be even higher, around 6 to 9 children per woman. There would be little reason to doubt that other groups at this time, near Rome were also experiencing similar if not identical challenges when it came to the composition of a ‘family’.

Taking all these factors into account, one Roman family of that time would look like:

The husband (33 years old) - experienced war veteran, no health insurance

The wife (23 years old) - experienced multiple childbirth deaths, PTSD

Potentially around 2-4 surviving children, majority entering teen years and ready to be put into marriage if female, or trained for war and labor - if male.

Going further, when we think of colonies or settlements by the Romans - these should be visualized on the same scale as the Celtic - Balkan migrations between 4th - 2nd Century BCE. Galatia, the most southern Celtic colony was founded by around 20,000 individuals, not solely men. Livy's account (Roman historian) clarifies that only half of this group, about 10,000, were armed warriors, in contrast to the much larger Celtic army in the Balkans in 279 BC, which numbered 150,000 infantry and 10,000–15,000 cavalry.

If Rome settled 3,000 families in 183 BC; by 169 BC (arrival of additional 1,500) the population of the initial 12,000 might be around 13,776 if you have a life expectancy rate between 22-32 and minimal allowed growth rate of 0.7%.

In 59 BC, the lex Vatinia granted Julius Caesar the role of proconsul over Gallia Cisalpina, Illyricum, and the command of three legions in Aquileia for five years. By 58 BC, the population of Aquileia would have been around 31,558 accounting for the added 1,500 families and 100 year time lapse with the same 0.7% growth rate. Additionally, upon the death of the proconsul of Gallia Narbonensis, Caesar was given control of that province and command over a stationed legion, also for five years.

In 58 BC, Caesar faced the challenging task of managing his proconsulships. While Gallia Narbonensis was a formal province, the other two, Gallia Cisalpina and Illyricum, were military command areas due to rebellions or threats. Liguria, prone to rebellion, and Bruttium, with unrest potential, had been designated similarly in the past. Caesar would go on to quell unrest in Gaul from 58 - 50 BC; Illyricum on the other hand turned to be a longer campaign that would be finished by another Roman.

In 48 BC, Caesar sent Cornificius to defend Illyricum against Pompey's supporters, who had taken refuge in the region. This is also the first time that we see a depiction of the land, Caesar described the region as impoverished and incapable of sustaining an army, attributing this condition to the conflicts in the Battle of Dyrrachium between him and Pompey, along with ongoing rebellions.

Cornificius, with the support of loyal locals, recovered Illyria. Meanwhile, Aulus Gabinius who was sent to assist but faced challenges, lost 2,000 soldiers, and retreated to Salona (Roman colony in Illyria), where he later died. Marcus Octavius sought to exploit the situation, prompting Cornificius to seek aid from Publius Vatinius. Vatinius, using makeshift ships from what is today Brindisi, Italy - thwarted Octavius's attacks, forcing him to retreat. In 45 BC, the Illyrians sought Caesar's alliance to avoid reprisals as they had been responsible for the death of Aulus Gabinius. Vatinius imposed a light tribute, but after Caesar's assassination in 44 BC, the Illyrians rebelled, routing Vatinius. Brutus later took control of Illyria during the Liberators' Civil War (43–42 BC).

Fearing retribution for routing Aulus Gabinius, the Illyrians sought an alliance with Caesar, anticipating his passage through their territory to reach Parthia. Caesar, unwilling to befriend them due to their past actions, offered forgiveness in exchange for a tribute and hostages. Despite the agreement, after Caesar's assassination in 44 BC and the ensuing chaos in Rome, the Illyrians no longer felt threatened by Roman authority. Ignoring Vatinius' attempts, they resisted forcefully, defeating his cohorts led by Baebius. Vatinius escaped to Dyrrhachium, and Caesar chose not to pursue the matter further. Appian suggested that Caesar had postponed addressing the Illyrian situation for fourteen years, despite holding command over Illyria and Gaul, and despite occasional Illyrian raids into northeastern Italy, due to engagements in the Gallic Wars, civil war, and planned conflict with Parthia.

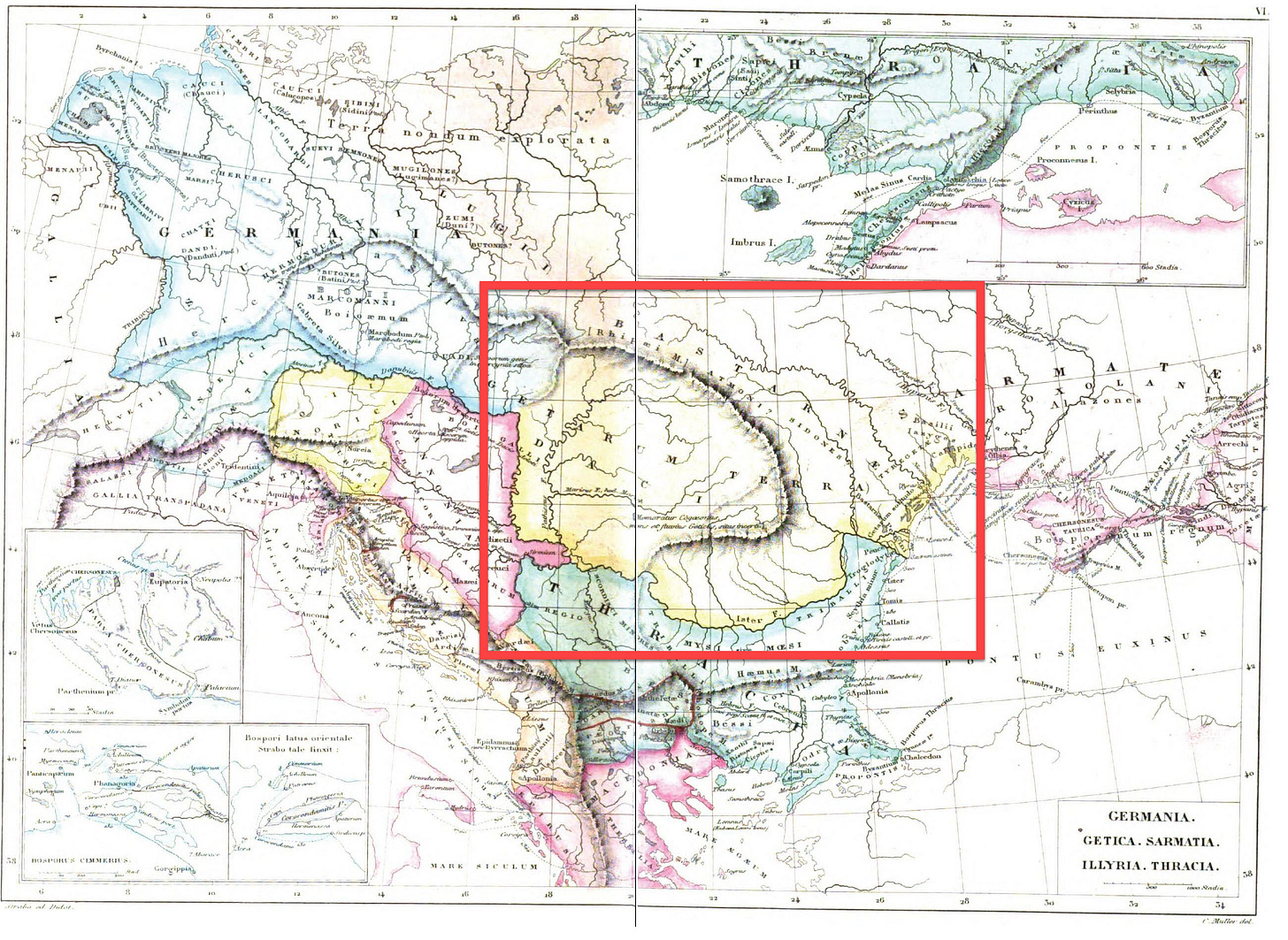

As Rome faced it’s internal problems and waged it majority in Illyricum, a new threat was growing from the Dacians on the other end of the Balkans; known as Getae in Greek and Dacus or Getae in Roman records. Unified by Burebista around 61 BC, the Dacians, influenced by Celtic, Scythian, and Thracian cultures, initiated conquest campaigns against neighboring tribes. In 60/59 BC, Burebista defeated the Boii and Taurisci tribes along the Middle Danube, expanding Dacian influence. The conflict led to the defeat of the Boii tribes around 50–40 BC, and Burebista also destroyed the Bastarnae. Further conquests included annexing Greek cities along the Black Sea coast from Olbia to Apollonia, with Dionysopolis maintaining friendly relations. An inscription in 48 BC described Akornion as Burebista's "first and greatest friend," and he was appointed as an ambassador to Pompey to secure the title of "king of kings" for Burebista in the Hellenistic kingdoms of the Balkans and the Near East. Ironically, had Burebista and Caesar not been assassinated by those beneath them, it would have been very likely that the Roman vs Dacian conflict would have reared much earlier than it did. Burebista turned his attention East, only outliving Caesar by a few months. But the foundation he created, would bloom decades later to impact the Balkans.

In the wake of Caesar's Civil War, the Liberators' Civil War, and the Sicilian Revolt led by Sextus Pompey, instability plagued Illyria, north-eastern Italy, and the Adriatic Sea. The Iapydes engaged in raids on north-eastern Italy, and piracy became a concern. Octavian, later Augustus (maternal great-nephew of Julius Caesar), embarked on campaigns in Illyricum from 35 BC, addressing various revolts and uprisings. Notable events include Octavian's campaigns against the Iapydes, the Metulians, the Segestani, and the Dalmatians, where he faced challenges, injuries, and prolonged sieges. His efforts culminated in the subjugation of these regions and other Illyrian tribes, bringing them under Roman rule. The conquest included dealing with rebellions, building fortifications and settlements, and accepting hostages. Octavian's victories extended to the islands of Melite and Melaina Corcyra, as well as suppressing piracy among the Liburnians. The completion of these campaigns in 34 BC marked the consolidation of Roman control over Illyricum and adjacent territories.

In 27 BC, Illyricum was established as a formal administrative province as part of the settlement that formalized Octavian's personal rule, leading to his honorary title of Augustus and the commencement of the Augustan age. The settlement delineated senatorial and imperial provinces, with the former governed by the senate and the latter under Augustus's direct appointment. Initially, Illyricum functioned as a senatorial propraetorial province, but due to rebellions, it transitioned to an imperial province in 11 BC, with Publius Cornelius Dolabella serving as its governor.

Pliny the Elder provides detailed insights into Illyricum's administrative structure. The coastal area was divided into three regions called "conventus juridicus," named after Scardona (Skradin), Salona, and Narona (near Metković). Urbanized coastal towns with Greek-speaking and Italian populations were organized as municipia or coloniae, enjoying self-governance. In the less urbanized interior, administration relied on civitates. The governor's jurisdiction was limited to the coastal area, while the inland districts had their governors, the praefecti civitatum. Pannonia was divided into 14 civitates, also functioning as a military district under the prefect of Pannonia. Dalmatia, strategically and economically vital, housed commercial ports, gold mines, and served as a crucial transit point for journeys across the Adriatic Sea. Dyrrachium and Brundisium were key ports, and towns like Iader, Salona, Narona, and Epidaurus played significant roles. The capital, Salona, had military protection from camps at Burnum and Delminium.

Between the campaigns of Augustus in 35–33 BC and 16 BC, Roman interest in Illyria waned. In 16 BC, Governor Publius Silius Nerva had to address disturbances in the Italian Alps, leaving Illyria vulnerable. Exploiting this opportunity, Pannonians and Noricans invaded Istria, prompting a swift response from Silius Nerva to restore order. Concurrently, a minor rebellion occurred in Dalmatia. The Dentheletae and Scordisci attacked Roman Macedonia, coinciding with a civil war in Thrace, creating instability in the eastern Alps and the Balkans. In 15 BC, Romans conquered the Scordisci, annexed Noricum, and carried out operations against the Rhaeti and Vindelici in the western Alps. Governor Marcus Vinicius in 14–13 BC likely initiated these military actions, leading to the transfer of Illyricum from a senatorial to an imperial province during the Pannonian war.

The Batonian War, a large-scale rebellion led by Bato the Daesitiate and Bato the Breucian, unfolded over four years (6–9 AD) and earned its name from the two leaders who shared the same name. In 6 AD, as the Romans prepared for a second expedition against the Marcomanni in Germania, a rebellion erupted under the leadership of Bato the Daesitiate, drawing on native auxiliary troops. Cassius Dio described the rebel force as Dalmatian, suggesting recruitment from various Dalmatian tribes. The Romans, sending a force to quell the rebellion, suffered defeat.

Simultaneously, Bato the Breucian, military leader of the Breuci, the largest tribe in southern Pannonia, marched on Sirmium but faced defeat by Aulus Caecina Severus, the governor of Moesia. Bato the Daesitiate, marching on Salona in Dalmatia, suffered defeat by Marcus Valerius Messalla Messallinus, the governor of Illyricum. The two Batos, regrouping, occupied Mount Alma but were defeated by a Thracian cavalry detachment supporting the Romans. The rebellion spread as the Dalmatians overran Roman ally territory, and Tiberius, in charge of the Roman army, led counterinsurgency operations against this elusive foe.

According to Velleius Paterculus, rebels divided forces into three parts, swiftly executing a plan that included invading Italy, entering the Roman Province of Macedonia, and fighting in their home territories. Massacres of Roman civilians and veterans ensued, creating a coordinated rebellion. In Cassius Dio's version, Bato the Daesitiate initially had few men, but his success increased his forces, forming an alliance with the other Bato after failing to take Salona. Rome faced panic, and Augustus called for levies, recalling veterans, and compelling rich families to supply freedmen.

In 7 AD, Augustus dispatched Germanicus to Illyricum. Rebels in Pannonia, facing Tiberius, were worn down, pushed to famine, and sought defensive positions in the Claudian Mountains. The second rebel force nearly inflicted a fatal defeat on Caecina Severus and Plautius Silvanus but was eventually repelled. Tiberius, facing overwhelming numbers, divided the Roman army into detachments, leading to a massive assembly. The army's size prompted Tiberius to send back newly arrived forces, and he returned to Siscia at the beginning of a harsh winter.

In 8 AD, Dalmatians and Pannonians sought peace, but rebels, desperate and unyielding, prevented a resolution. Tiberius implemented a scorched-earth policy, and Bato the Breucian overthrew Pinnes, the king of the Breuci. Bato the Daesitiate defeated and executed Bato the Breucian. Marcus Plautius Silvanus subdued Pannonian revolts without direct battle. Bato the Daesitiate withdrew from Pannonia, and Velleius Paterculus noted that the harsh winter eventually led to Pannonia seeking peace at the River Bathinus.

In 9 AD, the war focused on Dalmatia, with Augustus appointing Marcus Aemilius Lepidus as chief commander. Lepidus, moving through unaffected areas, faced local resistance but reached Tiberius. The campaign ended with the near extermination of the Perustae and Daesitiate tribes. Germanicus operated in Dalmatia, and Tiberius split the army to subdue areas, leading to the siege and surrender of Bato the Daesitiate. Cassius Dio recorded a poignant quote from Bato, blaming Romans for sending "wolves" instead of guardians for their flocks.

From their peak of 250 BC sea piracy, to being servants of Rome; all that was left of the Illyrian tribes after the Great Illyrian Revolt was the following (note, none of them larger than Aquileia):

Ardiaei

The Ardiaei, also known as Ouardaioi, were an Illyrian tribe residing inland. Eventually, they settled on the Adriatic coast and had 20 decuriae, equivalent to a measly 200 individuals. The Ardiaean dynasty ruled over the Illyrian Kingdom from it’s height in 250 BC.

Daorsi

The Daorsi, also known as Duersi or Daorsii, were an Illyrian tribe. They suffered attacks from the Delmatae, leading them to seek aid from the Roman state. After fighting on the Roman side in the Illyrian Wars, they were granted immunity. Their main city was Daorson, and they had 17 decuriae, equivalent to 170 individuals.

Deretini

The Deretini, or Derriopes, were an Illyrian tribe in Narona conventus with 14 decuriae, equivalent to 140 individuals.

Deuri

The Deuri, also known as Derbanoi, were an Illyrian tribe. After the Roman conquest, they had 25 decuriae in a conventus held in Salona, equivalent to 250 individuals.

Mazaei

The Mazaei, also known as Maezaei, were a tribal group with 269 decuriae, equivalent to 2,690 individuals.

Melcumani

The Melcumani, also known as Merromenoi or Melkomenioi, were an Illyrian tribe with 24 decuriae, equivalent to 240 individuals.

Narensi

The Narensi, a newly formed Illyrian tribe, had 102 decuriae, equivalent to 1,020 individuals. They were located around the River Naron or Neretva.

Siculotae

The Siculotae, also known as Sikoulotai, were an Illyrian tribe and part of the Pirustae. They had 24 decuriae, equivalent to 240 individuals.

Dalmatae

The Dalmatae were an ancient Illyrian tribe, later Celticized, with 342 decuriae, equivalent to 3,420 individuals.

Sardiatae

The Sardeates or Sardiotai were an Illyrian tribe close to Jajce. They later settled in Dacia and had 52 decuriae, equivalent to 520 individuals.

Docleatae

The Docleatae were an Illyrian tribe in present-day Montenegro with 33 decuriae, equivalent to 330 individuals. They were known for their cheese and formed after the Great Illyrian revolt.

Deraemestae

The Deraemestae were an Illyrian tribe composed of parts of several other tribes. They had 30 decuriae, equivalent to 300 individuals.

Daesitiates

The Daesitiates were an Illyrian tribe in central Bosnia and Herzegovina. Conquered by Roman Emperor Augustus, they were incorporated into the province of Illyricum with 103 decuriae, equivalent to 1,030 individuals.

Pirustae

The Pirustae or Pyrissaei were a Pannonian Illyrian tribe living in modern Montenegro. They later settled in Dacia and had connections to mining.

Scirtari

The Scirtari or Scirtones were an Illyrian tribe and part of the Pirustae with 72 decuriae, equivalent to 720 individuals.

Glintidiones

The Glintidiones were an Illyrian tribe, possibly part of the Pirustae, with 44 decuriae, equivalent to 440 individuals.

Ceraunii

The Ceraunii was an Illyrian tribe close to the Pirustae in modern Montenegro. They were part of the Pirustae and had 24 decuriae, equivalent to 240 individuals.

Maezaei

The Maezaei or Maizaioi were a Pannonian Illyrian tribe with 269 decuriae, equivalent to 2,690 individuals.

Ditiones

The Ditiones were a Pannonian Illyrian tribe with 239 decuriae, equivalent to 2,390 individuals.